How a school project developed into

a cultural icon for modern Irish music

by Êanna Dowling and Robert Allen

Kíla live in the Red Box, Dublin, November 16, 2004

review by Êanna Dowling

The Red Box is a venue decked out in the old Harcourt Street railway station in affluent Dublin. Outside, the new urban tram system the LUAS, (Gaelic word meaning speed) drops and picks suits and slaves in this nouveau business district. Inside 300 students are lashing back the smirnoff ice, red bull and shots of tequila, getting into the spirit of 'Trad Fest 2004'.

Trad Fest is a student week of socialising, celebrating traditional Irish music. It's put together by DITSU, the students union of the Dublin Institute of Technology, an amalgam of six campuses united by an Act of Parliament and events like this. The in-crowd wear branded t-shirts and butterfly around, passing vital information about the shifting and the pushing.

At the back of the hall, eight musicians watch three young girls stepping out on a raised platform, their peers whooping with enthusiasm. Riverdance has a lot to answer for. You'd never get long haired girls in immaculate make-up and shiny dresses when the Pogues, or even the Hot House Flowers, were Dublin's student house band. But tonight the Pogues are spun by the DJ between acts and one of the Flowers, Liam, is shuffling at the back with Kíla, ready to storm the stage.

Kíla are a busy band of comrades. They've visited 14 countries in 2004 including five trips to Spain. They've played in-your-face pub gigs, arts festival picnics and concerts in American theatres. They've released a live album to huge acclaim and they're keen to break a new young audience.

Kíla are a dance band, they want to see the crowd move, they've built their style on rhythmic roots, drawing in Irish, African and rock'n'roll flavours. They're big in Spain, they're used to fiesta. They're in the middle of one big fuck-off fiesta tonight.

I get a badge which means I can watch the show from the balcony with the support act and other Kíla friends. Just as well, cos it took over ten minutes to get a drink. Whiskey? Yeah. Really? Yeah. The bar is strewn with cans of red bull. And the bouncer wanted ID, and me in my thirties. I decided to feel flattered.

It's a small enough stage for eight people, but there's plenty of space for singer Rónán's dramatic swaying, backwards and forwards, the bodhrán up to his ear and him using the one of end of a slender stick to coax tunes out of it. Tonight he only sings a couple of songs. Some of the students sing along to Tog e go bog e (Take it Easy). Kíla sing in the Irish language, that's the first remarkable thing about them, they're big in Ireland, they're from Dublin and they sing in Irish. There's few enough bands from Dublin playing traditional music in an innovative way, but there's hardly anyone singing in Irish. The language is dying in the heartland, and growing slowly in pockets in the towns and cities. Tog e go bog e, bualfaimid aris ar ball - (see you later/take it easy/we'll meet up again later). The kids sing along, there's fists in the air. That's great, the kids know the tunes. Some of them weren't even born when Kíla were mastering Moving Hearts and Bothy Band covers.

I'm not sure why Liam is with the band tonight, but Rossa told me they're thinking of doing something funky, they have him in to see how it goes. The first time I saw Rónán sing, it was on a TV show with Liam. Liam had this piano and was exploring Irish roots through tunes. He introduced this fella, all hair and passion, who sang Feach! (Look!). Rónán stole the show, Liam played his best licks and I was hooked.

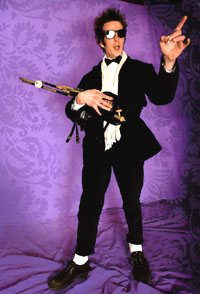

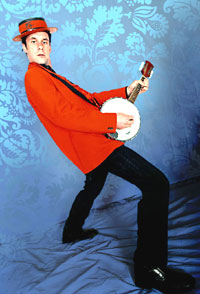

As the show winds up, Kíla members swop instruments. Over the course of a show a typical Kíla muso will play four or five instruments. There's a great percussion jam, the tune breaks down and the percussion, bodhrán and djembe, pick up the beat. Someone grabs a shaker, a friend jumps on stage and sits with another djembe, someone else settles at the congas. Liam is head banging away, the golden locks that seduced the late 1980s are flowing in the rhythm of the groove. He starts to finger a few chunky funky chord rifts. The red bull kids in the Red Box groove are Ireland's post rave generation, they know about dancing all night, they know about keeping it going. This is an acoustic rave, classy tunes played by excellent players, ahead of the game, sharing the spirit and connecting with the kids.

Kíla have a live album to promote, a Christmas concert to fill and lots of little mouths to feed. Even though their audience is pissed beyond composure, they still give their all, the sweat is pouring off them, band members kneel to the front of the stage to talk with the audience.

Kíla's arrangements provide them with space on stage for experimentation. The breakdown is getting trippy, the fiddle and the uileann pipes are riffing on the groove, the whistle and flute are soaring as the bodhrán, keyboard, guitar and bass keep it steady, ecstatically steady. Brian on the bass sticks his head out and yells out the one-two-three-four and the players gather back at the tune. These guys are tight, and why wouldn't they be after years on the road.

It could be a while before Kíla hit the road again so catch them if you can in Dublin on December 19.

Kíla combine excellent musicianship, great arrangements with a huge commitment to their audience. They have mastered a mighty style that connects Irish music, rock'n'roll, African, classical and gypsy elements into a wonderful swirl. The Kíla live experience - belonging, in the here and now, immediate and direct, life affirming and life enhancing.

|

|

|

Colm Ó Snodaigh - Flute, Tin Whistle, Guitar,

Djembe, Vocals, Percussion

Dee Armstrong - Fiddle, Viola, Hammered Dulcimer,

Accordion, Bodhrán

Lance Hogan - Guitar, Drum Kit, Djembe, Dumbeg,

Percussion, Vocals, Bass

Brian Hogan - Bass, Double Bass, Guitar,

Mandolin, Drums, Vocals

Eoin Dillon - Uileann Pipes, Tin Whistle, Low

Whistle, Shakers, Vocals

Rónán Ó Snodaigh - Bodhrán, Djembe, Congas,

Bongos, Guitar, Vocals

|

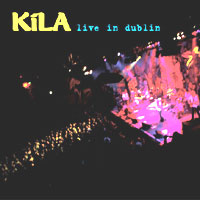

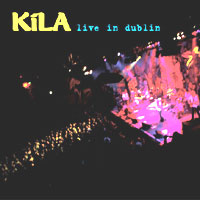

Kíla: Live in Dublin

CD review by Robert Allen

Kíla would be Ireland's best kept secret if they weren't known in many parts of the world as the Irish band that everyone wants to see. Pleas for gigs by fans in Australia, Canada, Israel ('Being Irish you wouldn't care about the bombs so much.'), Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the USA flood the Kíla forum on their website. (http://www.kila.ie)

Kíla are known as a live band, because gigging has been their bread and butter since they were formed seventeen years ago as a school project, and it is the live performance that Kíla live or die for. Their personal circumstances would dictate that this is the right time to release a live album but whether it will placate their demanding fans remains to be seen - because Kíla are more than live music, they are an experience. They are a band of the people for the people, which is evident by the banter from and to the stage. Capturing the essense of that experience is almost impossible, so the recorded live performance should be the next best thing.

Kíla, themselves, recognise this. They withdrew their 2000 Live release because they felt the quality was not up to scratch, so this second Live album has a lot to live up to. With half of the 11-track set from Luna Park, their multi-instrumental sound of 2003, those who have been attracted to Kíla by their dynamic, orchestral sound will snap it up. Those who like the trad in Kíla should also find it palatable. And those who like to be blown away by the rhythmic fusion of their music will wonder how they will survive a whole year without a Kíla gig.

The album starts with Her Royal Waggledy Toes, Cabhraighi Léi (Help Those) and Dusty Wine Bottle - three tunes that pay homage to Kíla's traditional roots. The mood changes with Tine Lasta (Fire Alight), a song from the Lemonade and Buns album from four years ago, when the band were starting to evolve with the sound that now sees them classified as 'world music' - a misnomer if there ever was one. This live version is a percussion train that is closer to techo than trad, and is the perfect foil for Bully's Acre that follows. Having warmed the audience nicely, Kíla settle into the comfort zone. This is trad with a gentle swing through the range of instruments that make Kíla the natural progression of Irish music in the 21st century - Chieftains, Moving Hearts, Kíla.

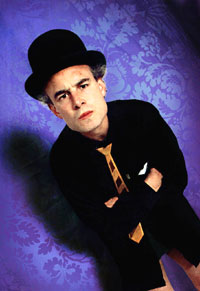

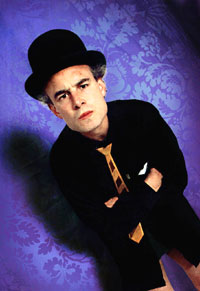

Wandering Fish, another track from Luna Park, slows things down even more. This is the soothing sound of Kíla, driven by a melody that flows with the sweet meanderings of the low whistle. The mood and tempo change immediately with Grand Hotel. A bodhrán beat leads a fast percussion into Eoin Dillon's uilleann pipes and that trippy sound Kíla have made their own on stage. It continues with all nine minutes and a bit of Glanfaidh Mé (I Will Clean) and a 12 minute version of Luna Park. This is the full elemental force of Kíla. They have a sound like no one else in Ireland and in Rónán Ó Snodaigh, who takes the vocals more often than not, they have a front man like no one else, because he sings 'as Gaeilge' [in Irish] and acts like a right eejit. Around him the band are wonderfully electric while he dances like a whirling dervish, and the sound they make is almost magical.

Irish is a poetic language that defies translation and when it is translated it loses its vital spirit. Somehow Kíla transcend this problem and whether you know Irish or not, the lyrics lift you up and away into a timeless land full of joyous music, the ballad and song of celtic Ireland in full fusion with the beat and rhythm of the outside world, whether it be Asia, Africa or America or the whole lot fused into one.

A reviewer once likened Kíla to 'a bunch of mad bastard warriors attacking over the hill' and said you'll struggle to find them in your local music store because there is no 'mad bastard warriors attacking over the hill rack, yet'. Yet. If this album doesn't bring Kíla wider recognition it's hard to know what will. Kíla's CDs have been going gold (7,500 sales) in Ireland in recent years, a sign that they are grabbing fans by the throat. Live in Dublin is another throat-grabbing experience and if you can't find it in your local store, go instead to the Mad Bastard Warriors Attacking Over The Hill Rack at their website. (http://www.kila.ie)

The secret's out.

Kíla would be Ireland's best kept secret if they weren't known in many parts of the world as the Irish band that everyone wants to see. Pleas for gigs by fans in Australia, Canada, Israel ('Being Irish you wouldn't care about the bombs so much.'), Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the USA flood the Kíla forum on their website. (http://www.kila.ie)

Kíla are known as a live band, because gigging has been their bread and butter since they were formed seventeen years ago as a school project, and it is the live performance that Kíla live or die for. Their personal circumstances would dictate that this is the right time to release a live album but whether it will placate their demanding fans remains to be seen - because Kíla are more than live music, they are an experience. They are a band of the people for the people, which is evident by the banter from and to the stage. Capturing the essense of that experience is almost impossible, so the recorded live performance should be the next best thing.

Kíla, themselves, recognise this. They withdrew their 2000 Live release because they felt the quality was not up to scratch, so this second Live album has a lot to live up to. With half of the 11-track set from Luna Park, their multi-instrumental sound of 2003, those who have been attracted to Kíla by their dynamic, orchestral sound will snap it up. Those who like the trad in Kíla should also find it palatable. And those who like to be blown away by the rhythmic fusion of their music will wonder how they will survive a whole year without a Kíla gig.

The album starts with Her Royal Waggledy Toes, Cabhraighi Léi (Help Those) and Dusty Wine Bottle - three tunes that pay homage to Kíla's traditional roots. The mood changes with Tine Lasta (Fire Alight), a song from the Lemonade and Buns album from four years ago, when the band were starting to evolve with the sound that now sees them classified as 'world music' - a misnomer if there ever was one. This live version is a percussion train that is closer to techo than trad, and is the perfect foil for Bully's Acre that follows. Having warmed the audience nicely, Kíla settle into the comfort zone. This is trad with a gentle swing through the range of instruments that make Kíla the natural progression of Irish music in the 21st century - Chieftains, Moving Hearts, Kíla.

Wandering Fish, another track from Luna Park, slows things down even more. This is the soothing sound of Kíla, driven by a melody that flows with the sweet meanderings of the low whistle. The mood and tempo change immediately with Grand Hotel. A bodhrán beat leads a fast percussion into Eoin Dillon's uilleann pipes and that trippy sound Kíla have made their own on stage. It continues with all nine minutes and a bit of Glanfaidh Mé (I Will Clean) and a 12 minute version of Luna Park. This is the full elemental force of Kíla. They have a sound like no one else in Ireland and in Rónán Ó Snodaigh, who takes the vocals more often than not, they have a front man like no one else, because he sings 'as Gaeilge' [in Irish] and acts like a right eejit. Around him the band are wonderfully electric while he dances like a whirling dervish, and the sound they make is almost magical.

Irish is a poetic language that defies translation and when it is translated it loses its vital spirit. Somehow Kíla transcend this problem and whether you know Irish or not, the lyrics lift you up and away into a timeless land full of joyous music, the ballad and song of celtic Ireland in full fusion with the beat and rhythm of the outside world, whether it be Asia, Africa or America or the whole lot fused into one.

A reviewer once likened Kíla to 'a bunch of mad bastard warriors attacking over the hill' and said you'll struggle to find them in your local music store because there is no 'mad bastard warriors attacking over the hill rack, yet'. Yet. If this album doesn't bring Kíla wider recognition it's hard to know what will. Kíla's CDs have been going gold (7,500 sales) in Ireland in recent years, a sign that they are grabbing fans by the throat. Live in Dublin is another throat-grabbing experience and if you can't find it in your local store, go instead to the Mad Bastard Warriors Attacking Over The Hill Rack at their website. (http://www.kila.ie)

The secret's out.

|

|

|

Kíla: An Introduction, by Robert Allen

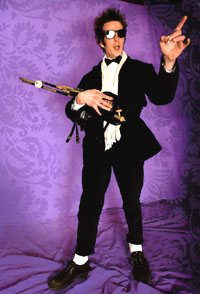

Kíla have provided the soundtrack to the positive, energised, compassionate response to the worst excesses of Tiger Ireland. The charismatic singer/songwriter and percussionist Rónán Ó Snodaigh sings in the native tongue of the Irish. The band incorporates traditional Irish rhythms and melodic idioms, gypsy tempo and tunes, structures from classical music, an African pulse and a rock'n'roll heart. They’re a dance band yet they can conjure a swell of tears from the heart of a grown man when they play their poignant airs. They travel the world playing in pubs, concert halls and outdoor festivals, gathering a community around them in the warmth of their performance. They are a co-operative, a community democracy even, and value the space they create for each of their seven members to make a positive contribution to the collective whole. Kíla are a group of hard working, smart, excellent musicians and very aware of the world that nurtures them and influences them.

They started back in October 1987 at Colaiste Eoin [in Stillorgan, Dublin], where some of the original band went to school. Rossa Ó Snodaigh is one of the original band members. 'There was a tradition in the school of having bands and you were allowed to play together and enter competitions. There were a few of us who had being playing since primary school together so we asked Eoin [Dillon] who was learning the pipes to join us and then we asked Rónán [Ó Snodaigh] who was playing the bodhrán.' The original line up was Eoin Dillon - uileann pipes; Colm Mac Con Iomaire - fiddle - Rossa Ó Snodaigh - whistle, bones; Rónán Ó Snodaigh - bodhrán.

Their music teacher Proinsias de Poire entered them in competitions under the name Cogar (meaning whisper). When Karl Odlum (bass) and his brother Dave (guitar) joined they felt they needed a name change. Rossa: 'We toyed with 'Setanta' and 'Cú Chulainn' (names of an Irish mythological hero) but these were deemed to be too like the names of the rebel song/ballad bands that were around at the time.'

They got their name change by a moment of serendipity. Rossa: 'We were approached by a French man, one Saturday, who had been listening to us busking. He asked if he could record us somewhere quieter so he could play us to these festival organisers back home. We arranged to meet him later in the oldest pub in Dublin, The Brazen Head. Being too young to be allowed to enter a bar we snuck in and hid down the back. The French man arrived and asked the barman whether we could play some music. He ordered us some pints and we started playing. After side A of his C60 tape was full he said he decided there was enough material there to convince his bosses. As he took details he asked us what we called ourselves. We paused not knowing what to say but Rónán just blurted out 'Keela'. The French man wrote down some spelling and he went away in a hurry. We never heard from him again and no festival ever contacted us but the barman liked our music so much that he invited us to do a Sunday afternoon session.'

Their first real gig was downstairs in the Baggot Inn. Three people turned up. They kept up the busking. It earned more. The following year Colm Ó Snodaigh joined the band for Kíla's first festival gig - in Germany. By October of 1988 they had performed live 47 times. Art exhibition openings, book launches and political gatherings made up many of them. Throughout 1989 and 1990 the Baggot was a regular gig along with the busking, which was split into two - those who played tunes at lunch time and those who played guitar, with hair, at tea time. To cap it all they played at the school's 20-year celebration in the National Concert Hall. They even got to make an album when they recorded 11 of Colm's songs.

It was time to put down some Kíla tunes, but first there was a band change. Dave Odlum and Colm Mac Con Iomaire left (to join The Frames). Dee Armstrong brought her fiddle and was joined by Dave Reidy and Eoin O’Brien on electric guitars. They recorded six tracks for a release called Groovin'. It was 1991 and the Letterkenny International Festival and Clifton Blues Festival beckoned. The following year, using the offices of Bord na Gaeilge (at night because the civil servants were distracted by the music during the day) they recorded Handel's Fantasy - without Dave Reidy. They had put down their first album, which was released on tape. Jazz bassist Ed Kelly joined. Rónán went off to perform alongside Lance Hogan with Dead Can Dance. Finding their groove the band recorded their second release, Mind the Gap. Brian Hogan was recruited to fill Ed Kelly's shoes, while he recovered from tendonitis. Then Kelly quit along with Eoin Ó Brien. Eoin Dillon moved to Donegal and they band thought they had lost him.

In 1995 Mind the Gap was released and they were joined by Lance Hogan (guitar and drums) and Laurence O'Keefe (bass). Kíla were about to take off. Tóg Ê go Bog Ê (Take it Easy) was recorded and released in 1997 along with the single Ón Taobh Tuathail Amach (From the Inside Out), which stopped at 24 in the charts. Kíla were on their way. By 2000 when their third album, Lemonade & Buns, was released they could say they had recorded music for Ballykissangel (a tv soap). Unfortunately for Kíla's prestige the project was scrapped. It didn't matter. The band were still on the rise. They recorded the soundtrack for the stage play, Monkey, 'much to the bemusement of [our] fans,' Kíla noticed. Then Luna Park was recorded and released in May 2003. Handel's Fantasy and Mind The Gap achieved gold status (7,500 sales). They were asked to play the Avalon stage in Glastonbury and were commissioned to compose music for the Special Olympics opening ceremony in Dublin but they also got to play to 80,000 at the All Ireland hurling final. In 2004 the band toured 14 countries in four continents. Luna Park went gold and their Kíla Live in Dublin album was released.

Kíla have come a long way to their success and it hasn't been easy. It has, to quote Rónán Ó Snodaigh, been organic, but it hasn't, to mention his brother Rossa, been without friction. Kíla are like no other band in Ireland. They have been influenced by traditional Irish music, by the Chieftains, the Bothy Band and Moving Hearts but their impact on modern Irish music is as modern as you can get, because they have taken influences from beyond the shores of Ireland. John Healy, the Mayo writer, once said he feared that Irish society would allow the modern world to 'sledgehammer its cultural values' into the minds of the youth. For the sledgehammer read techo yet Kíla have been able to take their traditional music and perform it with the energy and panache that the youth expect. It is not the sledgehammer that Healy feared but it is a cultural message. Rossa: 'We see the destruction that’s been done by people with more ambition than sense. Poverty in Ireland has made a lot of people very afraid for their future. It seems the wealthier people get, the meaner they get. When people are poor they seem to be able to share themselves with other people a lot easier. Once they have something, they have a responsibility and they don’t seem to want to deal with that responsibility. You see that in Ireland now, there's so many people with so much and with so little time to share with each other, I find that really just a shame. I thought we were really good as a country being poor, we’re not proving ourselves to be that good with money. Greed is taking over, house prices have taken over, now everyone’s mad keen to make enough money to pay the mortgage. The economy sped up and a lot of people were left behind, but a lot of people had time for each other and that was it, there was a great community, and that happens in most times there are hardship, people get together and club together. When there’s economics, people need a lot more, a lot more hanging out, a lot more getting together, people need a lot more support when their country’s rich.'

At the end of 2004, with five babies being born to the band, Kíla decided to take an 'inhalation', to record some studio albums and to reflect on seven years of 'globetrotting'.

Kíla have provided the soundtrack to the positive, energised, compassionate response to the worst excesses of Tiger Ireland. The charismatic singer/songwriter and percussionist Rónán Ó Snodaigh sings in the native tongue of the Irish. The band incorporates traditional Irish rhythms and melodic idioms, gypsy tempo and tunes, structures from classical music, an African pulse and a rock'n'roll heart. They’re a dance band yet they can conjure a swell of tears from the heart of a grown man when they play their poignant airs. They travel the world playing in pubs, concert halls and outdoor festivals, gathering a community around them in the warmth of their performance. They are a co-operative, a community democracy even, and value the space they create for each of their seven members to make a positive contribution to the collective whole. Kíla are a group of hard working, smart, excellent musicians and very aware of the world that nurtures them and influences them.

They started back in October 1987 at Colaiste Eoin [in Stillorgan, Dublin], where some of the original band went to school. Rossa Ó Snodaigh is one of the original band members. 'There was a tradition in the school of having bands and you were allowed to play together and enter competitions. There were a few of us who had being playing since primary school together so we asked Eoin [Dillon] who was learning the pipes to join us and then we asked Rónán [Ó Snodaigh] who was playing the bodhrán.' The original line up was Eoin Dillon - uileann pipes; Colm Mac Con Iomaire - fiddle - Rossa Ó Snodaigh - whistle, bones; Rónán Ó Snodaigh - bodhrán.

Their music teacher Proinsias de Poire entered them in competitions under the name Cogar (meaning whisper). When Karl Odlum (bass) and his brother Dave (guitar) joined they felt they needed a name change. Rossa: 'We toyed with 'Setanta' and 'Cú Chulainn' (names of an Irish mythological hero) but these were deemed to be too like the names of the rebel song/ballad bands that were around at the time.'

They got their name change by a moment of serendipity. Rossa: 'We were approached by a French man, one Saturday, who had been listening to us busking. He asked if he could record us somewhere quieter so he could play us to these festival organisers back home. We arranged to meet him later in the oldest pub in Dublin, The Brazen Head. Being too young to be allowed to enter a bar we snuck in and hid down the back. The French man arrived and asked the barman whether we could play some music. He ordered us some pints and we started playing. After side A of his C60 tape was full he said he decided there was enough material there to convince his bosses. As he took details he asked us what we called ourselves. We paused not knowing what to say but Rónán just blurted out 'Keela'. The French man wrote down some spelling and he went away in a hurry. We never heard from him again and no festival ever contacted us but the barman liked our music so much that he invited us to do a Sunday afternoon session.'

Their first real gig was downstairs in the Baggot Inn. Three people turned up. They kept up the busking. It earned more. The following year Colm Ó Snodaigh joined the band for Kíla's first festival gig - in Germany. By October of 1988 they had performed live 47 times. Art exhibition openings, book launches and political gatherings made up many of them. Throughout 1989 and 1990 the Baggot was a regular gig along with the busking, which was split into two - those who played tunes at lunch time and those who played guitar, with hair, at tea time. To cap it all they played at the school's 20-year celebration in the National Concert Hall. They even got to make an album when they recorded 11 of Colm's songs.

It was time to put down some Kíla tunes, but first there was a band change. Dave Odlum and Colm Mac Con Iomaire left (to join The Frames). Dee Armstrong brought her fiddle and was joined by Dave Reidy and Eoin O’Brien on electric guitars. They recorded six tracks for a release called Groovin'. It was 1991 and the Letterkenny International Festival and Clifton Blues Festival beckoned. The following year, using the offices of Bord na Gaeilge (at night because the civil servants were distracted by the music during the day) they recorded Handel's Fantasy - without Dave Reidy. They had put down their first album, which was released on tape. Jazz bassist Ed Kelly joined. Rónán went off to perform alongside Lance Hogan with Dead Can Dance. Finding their groove the band recorded their second release, Mind the Gap. Brian Hogan was recruited to fill Ed Kelly's shoes, while he recovered from tendonitis. Then Kelly quit along with Eoin Ó Brien. Eoin Dillon moved to Donegal and they band thought they had lost him.

In 1995 Mind the Gap was released and they were joined by Lance Hogan (guitar and drums) and Laurence O'Keefe (bass). Kíla were about to take off. Tóg Ê go Bog Ê (Take it Easy) was recorded and released in 1997 along with the single Ón Taobh Tuathail Amach (From the Inside Out), which stopped at 24 in the charts. Kíla were on their way. By 2000 when their third album, Lemonade & Buns, was released they could say they had recorded music for Ballykissangel (a tv soap). Unfortunately for Kíla's prestige the project was scrapped. It didn't matter. The band were still on the rise. They recorded the soundtrack for the stage play, Monkey, 'much to the bemusement of [our] fans,' Kíla noticed. Then Luna Park was recorded and released in May 2003. Handel's Fantasy and Mind The Gap achieved gold status (7,500 sales). They were asked to play the Avalon stage in Glastonbury and were commissioned to compose music for the Special Olympics opening ceremony in Dublin but they also got to play to 80,000 at the All Ireland hurling final. In 2004 the band toured 14 countries in four continents. Luna Park went gold and their Kíla Live in Dublin album was released.

Kíla have come a long way to their success and it hasn't been easy. It has, to quote Rónán Ó Snodaigh, been organic, but it hasn't, to mention his brother Rossa, been without friction. Kíla are like no other band in Ireland. They have been influenced by traditional Irish music, by the Chieftains, the Bothy Band and Moving Hearts but their impact on modern Irish music is as modern as you can get, because they have taken influences from beyond the shores of Ireland. John Healy, the Mayo writer, once said he feared that Irish society would allow the modern world to 'sledgehammer its cultural values' into the minds of the youth. For the sledgehammer read techo yet Kíla have been able to take their traditional music and perform it with the energy and panache that the youth expect. It is not the sledgehammer that Healy feared but it is a cultural message. Rossa: 'We see the destruction that’s been done by people with more ambition than sense. Poverty in Ireland has made a lot of people very afraid for their future. It seems the wealthier people get, the meaner they get. When people are poor they seem to be able to share themselves with other people a lot easier. Once they have something, they have a responsibility and they don’t seem to want to deal with that responsibility. You see that in Ireland now, there's so many people with so much and with so little time to share with each other, I find that really just a shame. I thought we were really good as a country being poor, we’re not proving ourselves to be that good with money. Greed is taking over, house prices have taken over, now everyone’s mad keen to make enough money to pay the mortgage. The economy sped up and a lot of people were left behind, but a lot of people had time for each other and that was it, there was a great community, and that happens in most times there are hardship, people get together and club together. When there’s economics, people need a lot more, a lot more hanging out, a lot more getting together, people need a lot more support when their country’s rich.'

At the end of 2004, with five babies being born to the band, Kíla decided to take an 'inhalation', to record some studio albums and to reflect on seven years of 'globetrotting'.

This is a working draft from the forthcoming

book, Ireland Unbound: From Byzantium to Beal

atha na Sluaighe, by Êanna Dowling and Robert

Allen, to be published in 2006.

Êanna Dowling meets Rossa Ó Snodaigh of Kíla in the Odeon Bar, Dublin, Tuesday, November 16, 2004

Rossa Ó Snodaigh - Tin Whistle, Low Whistle,

Clarinet, Bones, Bodhrán, Bongos, Congas, Djembe,

Didgeridoo, Bandooria, Darabuka, Percussion, Vocals

|

Blue: You're plugging the new Kila Live in Dublin album, is it going well for you?

Rossa: It's going brilliant. From having loads of Spanish people coming to our gigs for years, it turns out now that there's a Spanish DJ, who is like their John Peel. They call him 'The Pope'; he played the entire live album from start to finish on national radio in Spain, I mean national fucking radio fucking anywhere! Do you know?!?

Blue: For someone who listens to Kíla albums and goes to gigs, it sounds like there's a lot of work gone into the orchestration, it's not just diddly-aye tunes with the bodhrán going and the chords on the guitar, there's a lot of work gone into making it work.

Rossa: That's something that I feel sometimes, it seems to get overlooked by mainstream, anyone in mainstream media, it's something that they either say 'oh, it's not purist' - that's their only way of grappling with it and it's like. Of course people don't know how to grapple with the architecture of the arrangements. I mean there's great arrangements in pop music, but sometimes pop music is awful. It's a lot to do with trying to get your own spirit across as well.

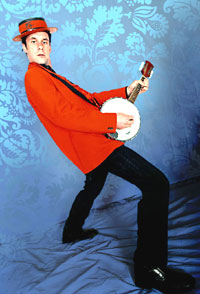

Blue: But one of the things that make Kíla distinctive as a musical thing is that you seem to put so much time into getting that right. I mean the breaks are right, the breakdowns are right, the variety of instruments that are played by the musicians during a gig, it's not like I'm the bass player and that's all I'm playing and shag off if you think I'm going to sing, there's none of that; it's like whatever the song needs, people chip in and do it so you get the fiddle player hitting the things on the percussion kit.

Rossa: That's exactly it, we're all chipping in to what's required If someone has a talent. Brian can play the bass and he's starting to come on to the drums an awful lot. He plays guitar as well. And Lance, he normally plays the guitar but originally he was a kit drummer and he has played bass on a few tracks. You can just learn your patterns on these instruments. And Colm was playing guitar. It's about getting everyone to fit in or to have something for everyone to do. There's seven of us, if there were five of us I'm sure there'd be less instrumentation. We've all got loads of ideas so it's about accommodation. What's amazing about it is that you can get all these incredible ideas, all these cross patterns, all these tonalities that are just really exciting and then okay sometimes it starts to get mushy and you start deleting some of the information - which we do very little of actually (laughs).

Blue: In the live context, sometimes the end of your songs just get trippy, there's no better word for it, just trippy, because you're all going for it, riffing on it and it just goes places. Do you know it's going to go there?

Rossa: Sometimes we allow the space for the music to get to those areas. When we started off, people would say 'you never finished your songs', because we'd get into the groove - boy you've got to prove your love to me, no. You'd get into the rhythm and it always felt wrong to cut it short. The arrangement, when you're rehearsing something, the arrangement goes to here and we just kept on playing it out, waiting for an end, and the end would never come, it would just kind of pitter out and we'd always make a hames of the bloody end.

So this is like back in the early 1990s and there's always that inclination. And then dance music hit. It didn't suit while there were people dancing and doing these three minute tracks. It just didn't suit. That would suit if you were a band that was well known and your records were on the radio. All those rhythm gigs - reels, polkas, hornpipes - though we don't do any of those, waltzes - they're all music to dance to. Lance and Brian, they don't come from that tradition, they're more familiar with rock'n'roll, Dee with classical music, so coming from that idiom, it always felt odd to be doing these three minute tunes and getting into this mad world of pop music. Then coming from the rock thing, which they had fitted into their environment for years.

Not wanting to, not getting anywhere in terms of commercial success for years, Irish music is for dancing to. Ceilis [community dances] were always for dancing and you'd always be dancing for eight or nine minutes at a set. There would be enough time for all the people to dance together and that would be part of the inclusion thing as well. You're informed by that and what we're up to now. Trad music came when Sean Ó Riada decided that he wanted to put music on the stage. He saw ceili bands, he didn't like the sound they were making but he loved the buzz. He saw how technically proficient everyone was at their instrument but they weren't really doing anything else other than everyone playing at the same time, all at the same time, doing the same thing, no arrangements, the only difference was the drummer. The drummer would be going - 'click click' - on the second part, on the first he'd go 'didl diddl didl didl (faster) which wasn't hugely successful as an aural kind of thing, it was great as a dancing thing. So I see ourselves as bringing back the revolution which was giving the music a structure. But then people were sitting, people just have it in a concert context where all these new musicians would go and listen to musicianship and listen to music and not just go and dance. I see what we're up is getting people back to dancing again, not just sitting and listening. And we're encouraging the architecture and the dance elements of the ceili bands and the trad bands.

Blue: You play in a variety of different locations. This year I would have seen you playing in Kilkenny in an outdoor gig and there most of the people are sitting down and it's a picnic and it's outdoor and it's family but there's still 50 people dancing and then you play in a place like The Vault in Cork where the whole pub would be going mad, and they can't help it, even if you're trying to sit down, everyone beside you is dancing.

Rossa: What happens is that over in America we're playing in these theatres, big grand theatres with 1,000 seats and we have to completely alter our set. We're doing breaks in the middle when our gigs are starting and we're building towards something by the end of the gig. We don't want to take a break in the middle at all so we do a lot of slow numbers, which we have a lot of. We suddenly realised that we have at least five waltzes and another three or four slow pieces that we're not paying attention to live on stage at all. So we're going to do an album with a whole load of slow pieces. And then do an album with a whole load of fast pieces. And maybe a song album. We've been mixing the three together. And creating something. But there's three separate directions there and enough material to pay attention to all of them.

Blue: On stage you always get one Colm song and two or three Rónán songs.

Rossa: Colm's songs seem to be more slow ballads and again Rónán has loads of slow ballads in English but they don't seem to fit into the set. Colm has loads of slow ballads in Irish that fill in. They're gorgeous and it's just a matter of sitting and giving them their proper arrangement. It's just trying to find that. Rónán's songs more easily lend themselves to percussion and rhythm, it's much easier to bring them to a live set.

Blue: He's probably writing them on bodhrán?

Rossa: Then having to break down and go into a song of Colm's which generally is really powerful and he's got an amazing voice. He's got a better voice for singing than Rónán but Rónán's voice has a better sound.

Blue: There's an edge to it

Rossa: It's a better sound for what he does in terms of the bodhrán stuff.

Blue: Can I bring you back to something? You just mentioned about Dee having the classical background and the boys having the rock thing going on and the Ó Snodaigh’s bringing in the trad stuff and it's working really well, but you're also taking in other stuff. It sounds to me like you're listening to other kinds of music, African music, gypsy music ...

Rossa: Totally yeah. Me and Dee years ago went over to WOMAD. She got wind in 1991 I think of this festival over in England called WOMAD. There was a percussion workshop and singing workshops and dance workshops. And that was a big eye opener. We had some Swedish fiddle music, Breton pipe bands and I used to listen to classical music as well. There were a lot of Chieftains albums, this was really early on, then you had all these musics coming, and you'd be listening to them, filtering in. Then Aonghus [Ó Snodaigh - older brother of Colm, Rónán and Rossa] went off to Korea. And he came back with Korean music. He went off lecturing there or studying there or something. South or North [Korea], I can't remember ... but this is when he was in college. We'd always get my parents to bring back music. So when we had a chance to go over to this world music festival and get a chance to learn percussion from around the world, we bloody hopped it. We hitched over on the boat, damn all money. We were really lucky, the first day there. I found a fecking hundred pound note on the ground. And stupidly told people that we'd found it and luckily nobody claimed it (laughs).

Blue: You were in the clear

Rossa: We were in the clear and a hundred quid up. So that was an eye opener seeing these musicians from all over the world and there was a whole idea that accompanied Irish music was like, you shouldn't be doing that, much as even though The Bothy Band were there, Moving Hearts had done it, Stockton's Wing were there, even though Horslips had done it, even though Mushroom had done it, even though countless numbers of bands had done it, it was like the way you should be going is solo. So.

Blue: Were you tempted by that solo artist career?

Rossa: No, no, not at all, we'd added bass and the guitar in 1987 anyway. I didn't know what the sound was. A friend of mine, one of the guys who was in the band in school around 1985, said listen to the bass and I'm going 'what's the bass?' We suddenly realised that we could play like fucking Moving Hearts! Great! We started covering their stuff. We started doing Bothy Band covers and trying to get their arrangements, emulating what they were up to.

Blue: And would early Kila gigs have had those tunes in them?

Rossa: Oh yeah yeah ... but Dave Odlum at the time said, 'no I don't want to play just like Moving Hearts, I want to play our own stuff' and I was going eh, how do you do that? And Rónán said, 'Listen I don't want to be playing anyone else's music, I want to be playing our own music, we're writing enough tunes ourselves,' and then we started writing our own tunes. I started seeing that there were these people who were matching African music, South American music, Latin American music, Korean music. They were adding arrangements that suited the music that wasn't rock'n'roll just added on top of it. I started realising that a lot of the arrangements they had would suit Irish music a lot more. The patterns had gone through a process of a thousand years, much like Irish music. Whereas rock'n'roll is the distillation and the simplification of a lot of music, this stuff is a lot of the other music.

Folk music is still carrying on, but the flavours are more complex. Rock'n'roll is a very young wine, the flavours aren't very complex, and folk music tends to be very complex. So I saw that and realised that Irish music is rhythmically complex and to put a one-two-three-four rock beat behind it, generally doesn't work, generally it's a full stop after every four bars, whereas Irish music is all about the rhythmic fluidity, never ever putting a stop in. You have to hide your breath when you're playing a whistle because you want it to be constant, constantly moving.

And always reinterpreting how else you can express this rhythm while keeping it interesting to my own ears, cos I was playing the bones as well. The amount of pulses within a certain rhythm is huge because you have two sticks kind of clacking, doing sixteenths on each of them. I went up to Ken [Samson, a Maori percussionist, in Galway] and said, 'can I join the session?' And he looked at me and he went 'no'. And I went hang on a minute, this is someone with an accent I don't know, not from Ireland, telling me I can't join in a fucking session! So I asked the bodhrán player. 'I want to play your bongos.' and he went, the way most Irish people do, he won't say no, to hold face, and then I saw it as a competition cos this guy was doing quite simple rhythms and I'm going ... I'm going to lash this guy out of it. So it was a real battle and I sat down and started playing the bongos and started throwing in rhythms and he didn't know where I was coming from. He was totally shocked because he thought I was going to be one of these kind of djembe session wreckers. So we started getting louder and louder and at the end of the session the bodhrán player is saying, 'lads do you mind, keeping the drums down just for the next tune!' (Laughs.) And so then that was it, I had a friend in Ken. Years previously it would have been a sword challenge, this was a rhythm challenge!

Blue: I'm very interested in the concept of Kíla as a community and how you all work together. You've been together for a long time as a band and you have a lot of other responsibilities and things going on. There's so much creativity and so little space there must be some nitty gritty from time to time.

Rossa: There’s always friction but you don’t get creativity without friction. You don’t get things going on in a placid, you don’t get waves in a placid lake. So of course there’s friction, that’s the joy of it, finding a compromise, and sometimes that's what we tend to do. It’s fucking much like a co-operative. We were always wary starting out, we had no interest from record companies, we had no one offering us money and initially we were just this band getting gigs and rehearsing and that was sustaining us. Well actually it was the dole that was sustaining us. We were government artists, drawing the dole, ha.

Blue: Sure it was the 90s and everyone was sustained by it. It was a time when 17-20% of the people were unemployed either legit or illegit.

Rossa: People were leaving the country and I didn’t want to leave Ireland, I was having good fun here, but everyone else was looking for a 9 to 5 elsewhere outside Ireland, I didn’t really see that as my thing. I wanted to be an actor, actually, and I did acting courses and got some extra jobs, here and there.

Blue: But you're making a living from what you like doing, which is way ahead of the game

Rossa: Yeah, we decided to work as a co-operative and the money that's made now is put into a pool and we each get the same money every week, even though there's more made the one week and less made the next week, Sometimes we go three weeks where we wouldn’t gig but the money would still be coming in. It means we can just about sustain ourselves. But it’s getting really tight. I don’t know how much more we can afford in terms of prices of everything. You get a paper, a bit of bread a couple of croissants and you’re forking out a fiver, maybe six quid.

Blue: Combat Poverty Agency would be similarly minded to yourself in that they would say that if you're a single mom and you're reliant on the State, you're shagged financially, it's just tight.

Rossa: Even now, there’s a friend of mine, she’s pregnant and she rang up and she said, 'I’m not going to be able to sign on because I’m going to be in hospital' and they said, 'oh well then you won’t be eligible for your dole, you’re not actively seeking work if you’re in hospital', and the same happened to me. I had an operation on my knee and they told me because I missed signing on the dole that I was ineligible for it. There's this kind of mentality that if you're down they want to keep you down, I thought FAS [work scheme] was really good but they're taking away a lot of those CE [more work] schemes now because they feel people are dependent on them, which they are! They are dependent on them!

Blue: Did Kíla as a business ever get any State assistance to keep you going?

Rossa: Not a fucking ... We were trying. We didn’t have the business acumen to figure out [government assistance]. I remember we did once approach the IDA. We have to get some fucking money to keep this thing running. We were promised some money from some group in March, promised it back in March and they only got back to us recently saying they're not giving it to us. I mean this is all in projections and cashflows and you're just going no, that's just wrong of them! We’ve asked the Arts Council, we’ve asked them over the years, and we've consistently not even been answered so now they have a policy on traditional music, they might give it to us.

Blue: They mightn't see you as traditional enough?

Rossa: The whole problem though is that traditional music is only thought of in the terms of the English language. Traditional meaning handed down. But traditional also means accustomed. I’m thinking of traditional meaning a host of other things. But there's a whole group of people who say traditional music means handed down, so if you’re writing new tunes you're not traditional, which is fucking ridiculous, cos there is a tradition of composition within what is called traditional music so I’m calling it Ceol Gaelach [Irish music] and I wrote an article talking about the three branches: there was the purist trad; there were the trad bands, which is your pub trad and the more acoustic arrangements; and then you have your nua [new] trad. I didn’t see that there was any difference because it enters into the creative, the creative accompaniment. If you start tapping your fingers, that's accompaniment, and you just bring that to a bigger place. It shouldn’t have to be ... it's like people who use two colours and say did you ever see that film, which was very funny, a great metaphor. They were saying no colours allowed, it was all black and white and set in the 50s. People were suddenly seeing the light and started having colours on them. And there was a big thing, no colours allowed, and it was all this black and white people kind of fearing for their lives of colourful people. It was 'classic city' - some simple story that could be adapted to any situation where there's revolution, where there's change, where there's a new outlook versus an old outlook and the old outlook gets threatened and their outlook with its strict structures was always correct and should always remain.

Like there are traditional musicians in Kíla. I always wanted to be really good on the whistle. Colm wanted to be really great on the flute and the people we looked up to were great musicians who came from the tradition. But once there were seven of us around it just became more exciting than trying to emulate or be as good as a solo musician. So it’s like, let’s see what we can do. Our heroes were Moving Hearts, Donal Lunny’s band, which he put together for the O’Riada retrospective, and then starting to hear all these other bands from around the world from Brittany, from Scotland, doing these amazing stuff with tunes, similar rhythmic idioms - most of the rhythmic idioms came from outside of Ireland anyway. Dance teachers who were travelling learning a certain dance form and would bring it down and the funny thing is that the hornpipe came from England, from English soldiers, who came over here in the 18th century, the accordion was only created in the 18th century, the Polka came from Poland or somewhere in Europe and it was most resisted down in Kerry which is now the home of the Polka. Kind of odd, you know.

Blue: Would that be an expression of a Dublin/Ireland division too?

Rossa: I do see a city thing, a city thing in the way we see music, there's a lot of influences and we're being true to our influences. We went to sleep to wind in the trees, the sea (we were by the sea), and traffic passing, Lance and Brian were also by the seaside, Eoin was in a relatively quieter area. But a lot of other trad musicians, young purists I’d call them, they went to sleep to silence out in west Clare and that's natural to them, but they seem to think that just because they were from west Clare their music is more authentic and more true to… and it's not, it's not any truer. I see ourselves as a product of the city.

Blue: Do you have an audience in rural Ireland?

Rossa: Yeah. People come to our gigs listen and dance. Years ago we used to play in Belfast and they wouldn't listen. They'd be shouting and we'd be kind of going 'what is going on here' and we'd stop. And next they'd be shouting for more! What the hell were they listening to if they want more of it. You’d be playing your slow tune and there'd be 20 people roaring at each other. And the same people would be roaring at you to keep going so yeah in a way at the time it was a backdrop to their blabbering.

Blue: One of the things that Kila gigs do is give people a space to hang out and connect with each other. People respond to the use of the Irish language in the band, or maybe the use of different cultures in the music or maybe just the craic and the buzz, but a Kíla gig is a gig you go to meet people. People meet, they have a good time, connect, there's a shared belief system, a sense of community in your audience. Is it fair enough to say that?

Rossa: I would say that, if someone was to do a 'what type comes to Kíla?' they'd find bloody every type, but there's a strong kind of element from people with love of country, and that being love of environment, love of the language, love of the culture and then people who have love of other culture, extended love of country but not in a negative way but extended outwards ... love in the terms of respect really and hope, hope for the environment, hope for the culture, hope for the country. That would probably be the way you'd see love in any of this and hope for other people. That’s my own view. It’s funny how your own views can attract other people through musical notes, without saying a thing! [Laughs] It becomes like the lads you’re hanging out with and hey we've got a gig and they bring their mates and before you know it you’ve got a gathering.

Blue: Maybe that's the way Kila developed in the early days it was a word of mouth phenomenon, there was no big marketing campaign to let Kila know

Rossa: It was a word of mouth phenomenon and we did put posters on the backs of buses and on windows of big offices, we were reprimanded by the council, [laughs] we were charged a hundred pounds for littering. But yeah, it was word of mouth and we were producing our own albums back then. My dad and mum, my dad’s a publisher of, constantly puts out Irish language books, my mum’s an artist and a sculptor, and she was always putting on exhibitions, that wasn't new to us. A lot of bands are immediately defeated by the fact that they have to record, or they're defeated once they've done the recording by the fact that they have to promote it, they're defeated then by the fact that they have to play live. We were lucky because we grew up seeing people doing it all the time. So someone writes a book and you get the book published and then you’re on to the next one. And there’s always a sense of being creative all the time anyway. We were lucky in that sense.

Blue: That DIY culture, that's still in the band, you're still financing your own albums, I mean you're dependent on your own sales, you're not getting a few grand up front?

Rossa: No, no we did get loans. RMG [distributor] having seen that we were selling enough CDs over the years, would say 'ok we can front you enough money to press the CD because we know you're going to sell this amount of CDs'. So they help us out, Vicar Street helped us out, they said we'll give us x amount of money, we'll take it out of your Christmas gig and we had to take a lot of loans, we’re still paying them off.

Blue: Do the band participate in those decisions, do you sit around and decide what you're going to do?

Rossa: Decision-making can be very difficult in the band because there’s always someone who hasn’t a clue what it's about, it could be me, it could be anyone. It has to be reiterated again and again. Sarah now is our manager, but Colm has been basically managing us through all the other managers we’ve had. Teaching them the ropes, showing them who's been speaking to who and dealing with licensing deals around the world Basically we're a cottage industry with a lot of goodwill from a lot of people. A friend of mine setting up, doing a website for us, friends doing videos for us and us being able to give them enough money to cover the costs of this and that.

As much as we’re giving people a chance, it helps their CV in a way to be taking photos of a live band and we’d also like to have them paid, and when people do support generally we want to pay people who play before us because they’re entertaining our guests and you can't be asking people to turn up and do things for no money though we're always doing that for charity. We’ve constantly played for different charities and there was one stage, I think it was seven years ago, there were more charity gigs being asked of us than there were paid gigs and you just have to start saying we can’t. You're kind of going no, we have to survive here, we have to draw the line.

Blue: Sometimes you get a mini Kíla.

Rossa: We had to make the decision that we can’t be writing Kíla if it's only going to be half of us because it's unfair to people who are expecting Kíla.

Blue: You're a busy bunch of lads

Rossa: We're taking a break off the road because we're just bloody exhausted. Five of us will have had kids this year [2004] and we're going to try and take a big inhalation before the next exhalation. As a band we’ve been seven years globetrotting, 14 countries [in 2004], nine countries [in 2003], full on!

Blue: Thanks very much, will we leave it there, thanks for the insights and the chat; I'd say there's no stopping you once you get going ...

Rossa: Laughs ...

![]()

Photographs courtesy of Kíla. Thanks to Sarah

Glenanne, Colm Ó Snodaigh and Rossa Ó Snodaigh.

|

|

Kíla have provided the soundtrack to the positive, energised, compassionate response to the worst excesses of Tiger Ireland. The charismatic singer/songwriter and percussionist Rónán Ó Snodaigh sings in the native tongue of the Irish. The band incorporates traditional Irish rhythms and melodic idioms, gypsy tempo and tunes, structures from classical music, an African pulse and a rock'n'roll heart. They’re a dance band yet they can conjure a swell of tears from the heart of a grown man when they play their poignant airs. They travel the world playing in pubs, concert halls and outdoor festivals, gathering a community around them in the warmth of their performance. They are a co-operative, a community democracy even, and value the space they create for each of their seven members to make a positive contribution to the collective whole. Kíla are a group of hard working, smart, excellent musicians and very aware of the world that nurtures them and influences them.

They started back in October 1987 at Colaiste Eoin [in Stillorgan, Dublin], where some of the original band went to school. Rossa Ó Snodaigh is one of the original band members. 'There was a tradition in the school of having bands and you were allowed to play together and enter competitions. There were a few of us who had being playing since primary school together so we asked Eoin [Dillon] who was learning the pipes to join us and then we asked Rónán [Ó Snodaigh] who was playing the bodhrán.' The original line up was Eoin Dillon - uileann pipes; Colm Mac Con Iomaire - fiddle - Rossa Ó Snodaigh - whistle, bones; Rónán Ó Snodaigh - bodhrán.

Their music teacher Proinsias de Poire entered them in competitions under the name Cogar (meaning whisper). When Karl Odlum (bass) and his brother Dave (guitar) joined they felt they needed a name change. Rossa: 'We toyed with 'Setanta' and 'Cú Chulainn' (names of an Irish mythological hero) but these were deemed to be too like the names of the rebel song/ballad bands that were around at the time.'

They got their name change by a moment of serendipity. Rossa: 'We were approached by a French man, one Saturday, who had been listening to us busking. He asked if he could record us somewhere quieter so he could play us to these festival organisers back home. We arranged to meet him later in the oldest pub in Dublin, The Brazen Head. Being too young to be allowed to enter a bar we snuck in and hid down the back. The French man arrived and asked the barman whether we could play some music. He ordered us some pints and we started playing. After side A of his C60 tape was full he said he decided there was enough material there to convince his bosses. As he took details he asked us what we called ourselves. We paused not knowing what to say but Rónán just blurted out 'Keela'. The French man wrote down some spelling and he went away in a hurry. We never heard from him again and no festival ever contacted us but the barman liked our music so much that he invited us to do a Sunday afternoon session.'

Their first real gig was downstairs in the Baggot Inn. Three people turned up. They kept up the busking. It earned more. The following year Colm Ó Snodaigh joined the band for Kíla's first festival gig - in Germany. By October of 1988 they had performed live 47 times. Art exhibition openings, book launches and political gatherings made up many of them. Throughout 1989 and 1990 the Baggot was a regular gig along with the busking, which was split into two - those who played tunes at lunch time and those who played guitar, with hair, at tea time. To cap it all they played at the school's 20-year celebration in the National Concert Hall. They even got to make an album when they recorded 11 of Colm's songs.

It was time to put down some Kíla tunes, but first there was a band change. Dave Odlum and Colm Mac Con Iomaire left (to join The Frames). Dee Armstrong brought her fiddle and was joined by Dave Reidy and Eoin O’Brien on electric guitars. They recorded six tracks for a release called Groovin'. It was 1991 and the Letterkenny International Festival and Clifton Blues Festival beckoned. The following year, using the offices of Bord na Gaeilge (at night because the civil servants were distracted by the music during the day) they recorded Handel's Fantasy - without Dave Reidy. They had put down their first album, which was released on tape. Jazz bassist Ed Kelly joined. Rónán went off to perform alongside Lance Hogan with Dead Can Dance. Finding their groove the band recorded their second release, Mind the Gap. Brian Hogan was recruited to fill Ed Kelly's shoes, while he recovered from tendonitis. Then Kelly quit along with Eoin Ó Brien. Eoin Dillon moved to Donegal and they band thought they had lost him.

In 1995 Mind the Gap was released and they were joined by Lance Hogan (guitar and drums) and Laurence O'Keefe (bass). Kíla were about to take off. Tóg Ê go Bog Ê (Take it Easy) was recorded and released in 1997 along with the single Ón Taobh Tuathail Amach (From the Inside Out), which stopped at 24 in the charts. Kíla were on their way. By 2000 when their third album, Lemonade & Buns, was released they could say they had recorded music for Ballykissangel (a tv soap). Unfortunately for Kíla's prestige the project was scrapped. It didn't matter. The band were still on the rise. They recorded the soundtrack for the stage play, Monkey, 'much to the bemusement of [our] fans,' Kíla noticed. Then Luna Park was recorded and released in May 2003. Handel's Fantasy and Mind The Gap achieved gold status (7,500 sales). They were asked to play the Avalon stage in Glastonbury and were commissioned to compose music for the Special Olympics opening ceremony in Dublin but they also got to play to 80,000 at the All Ireland hurling final. In 2004 the band toured 14 countries in four continents. Luna Park went gold and their Kíla Live in Dublin album was released.

Kíla have come a long way to their success and it hasn't been easy. It has, to quote Rónán Ó Snodaigh, been organic, but it hasn't, to mention his brother Rossa, been without friction. Kíla are like no other band in Ireland. They have been influenced by traditional Irish music, by the Chieftains, the Bothy Band and Moving Hearts but their impact on modern Irish music is as modern as you can get, because they have taken influences from beyond the shores of Ireland. John Healy, the Mayo writer, once said he feared that Irish society would allow the modern world to 'sledgehammer its cultural values' into the minds of the youth. For the sledgehammer read techo yet Kíla have been able to take their traditional music and perform it with the energy and panache that the youth expect. It is not the sledgehammer that Healy feared but it is a cultural message. Rossa: 'We see the destruction that’s been done by people with more ambition than sense. Poverty in Ireland has made a lot of people very afraid for their future. It seems the wealthier people get, the meaner they get. When people are poor they seem to be able to share themselves with other people a lot easier. Once they have something, they have a responsibility and they don’t seem to want to deal with that responsibility. You see that in Ireland now, there's so many people with so much and with so little time to share with each other, I find that really just a shame. I thought we were really good as a country being poor, we’re not proving ourselves to be that good with money. Greed is taking over, house prices have taken over, now everyone’s mad keen to make enough money to pay the mortgage. The economy sped up and a lot of people were left behind, but a lot of people had time for each other and that was it, there was a great community, and that happens in most times there are hardship, people get together and club together. When there’s economics, people need a lot more, a lot more hanging out, a lot more getting together, people need a lot more support when their country’s rich.'

At the end of 2004, with five babies being born to the band, Kíla decided to take an 'inhalation', to record some studio albums and to reflect on seven years of 'globetrotting'.

Kíla have provided the soundtrack to the positive, energised, compassionate response to the worst excesses of Tiger Ireland. The charismatic singer/songwriter and percussionist Rónán Ó Snodaigh sings in the native tongue of the Irish. The band incorporates traditional Irish rhythms and melodic idioms, gypsy tempo and tunes, structures from classical music, an African pulse and a rock'n'roll heart. They’re a dance band yet they can conjure a swell of tears from the heart of a grown man when they play their poignant airs. They travel the world playing in pubs, concert halls and outdoor festivals, gathering a community around them in the warmth of their performance. They are a co-operative, a community democracy even, and value the space they create for each of their seven members to make a positive contribution to the collective whole. Kíla are a group of hard working, smart, excellent musicians and very aware of the world that nurtures them and influences them.

They started back in October 1987 at Colaiste Eoin [in Stillorgan, Dublin], where some of the original band went to school. Rossa Ó Snodaigh is one of the original band members. 'There was a tradition in the school of having bands and you were allowed to play together and enter competitions. There were a few of us who had being playing since primary school together so we asked Eoin [Dillon] who was learning the pipes to join us and then we asked Rónán [Ó Snodaigh] who was playing the bodhrán.' The original line up was Eoin Dillon - uileann pipes; Colm Mac Con Iomaire - fiddle - Rossa Ó Snodaigh - whistle, bones; Rónán Ó Snodaigh - bodhrán.

Their music teacher Proinsias de Poire entered them in competitions under the name Cogar (meaning whisper). When Karl Odlum (bass) and his brother Dave (guitar) joined they felt they needed a name change. Rossa: 'We toyed with 'Setanta' and 'Cú Chulainn' (names of an Irish mythological hero) but these were deemed to be too like the names of the rebel song/ballad bands that were around at the time.'

They got their name change by a moment of serendipity. Rossa: 'We were approached by a French man, one Saturday, who had been listening to us busking. He asked if he could record us somewhere quieter so he could play us to these festival organisers back home. We arranged to meet him later in the oldest pub in Dublin, The Brazen Head. Being too young to be allowed to enter a bar we snuck in and hid down the back. The French man arrived and asked the barman whether we could play some music. He ordered us some pints and we started playing. After side A of his C60 tape was full he said he decided there was enough material there to convince his bosses. As he took details he asked us what we called ourselves. We paused not knowing what to say but Rónán just blurted out 'Keela'. The French man wrote down some spelling and he went away in a hurry. We never heard from him again and no festival ever contacted us but the barman liked our music so much that he invited us to do a Sunday afternoon session.'

Their first real gig was downstairs in the Baggot Inn. Three people turned up. They kept up the busking. It earned more. The following year Colm Ó Snodaigh joined the band for Kíla's first festival gig - in Germany. By October of 1988 they had performed live 47 times. Art exhibition openings, book launches and political gatherings made up many of them. Throughout 1989 and 1990 the Baggot was a regular gig along with the busking, which was split into two - those who played tunes at lunch time and those who played guitar, with hair, at tea time. To cap it all they played at the school's 20-year celebration in the National Concert Hall. They even got to make an album when they recorded 11 of Colm's songs.

It was time to put down some Kíla tunes, but first there was a band change. Dave Odlum and Colm Mac Con Iomaire left (to join The Frames). Dee Armstrong brought her fiddle and was joined by Dave Reidy and Eoin O’Brien on electric guitars. They recorded six tracks for a release called Groovin'. It was 1991 and the Letterkenny International Festival and Clifton Blues Festival beckoned. The following year, using the offices of Bord na Gaeilge (at night because the civil servants were distracted by the music during the day) they recorded Handel's Fantasy - without Dave Reidy. They had put down their first album, which was released on tape. Jazz bassist Ed Kelly joined. Rónán went off to perform alongside Lance Hogan with Dead Can Dance. Finding their groove the band recorded their second release, Mind the Gap. Brian Hogan was recruited to fill Ed Kelly's shoes, while he recovered from tendonitis. Then Kelly quit along with Eoin Ó Brien. Eoin Dillon moved to Donegal and they band thought they had lost him.

In 1995 Mind the Gap was released and they were joined by Lance Hogan (guitar and drums) and Laurence O'Keefe (bass). Kíla were about to take off. Tóg Ê go Bog Ê (Take it Easy) was recorded and released in 1997 along with the single Ón Taobh Tuathail Amach (From the Inside Out), which stopped at 24 in the charts. Kíla were on their way. By 2000 when their third album, Lemonade & Buns, was released they could say they had recorded music for Ballykissangel (a tv soap). Unfortunately for Kíla's prestige the project was scrapped. It didn't matter. The band were still on the rise. They recorded the soundtrack for the stage play, Monkey, 'much to the bemusement of [our] fans,' Kíla noticed. Then Luna Park was recorded and released in May 2003. Handel's Fantasy and Mind The Gap achieved gold status (7,500 sales). They were asked to play the Avalon stage in Glastonbury and were commissioned to compose music for the Special Olympics opening ceremony in Dublin but they also got to play to 80,000 at the All Ireland hurling final. In 2004 the band toured 14 countries in four continents. Luna Park went gold and their Kíla Live in Dublin album was released.

Kíla have come a long way to their success and it hasn't been easy. It has, to quote Rónán Ó Snodaigh, been organic, but it hasn't, to mention his brother Rossa, been without friction. Kíla are like no other band in Ireland. They have been influenced by traditional Irish music, by the Chieftains, the Bothy Band and Moving Hearts but their impact on modern Irish music is as modern as you can get, because they have taken influences from beyond the shores of Ireland. John Healy, the Mayo writer, once said he feared that Irish society would allow the modern world to 'sledgehammer its cultural values' into the minds of the youth. For the sledgehammer read techo yet Kíla have been able to take their traditional music and perform it with the energy and panache that the youth expect. It is not the sledgehammer that Healy feared but it is a cultural message. Rossa: 'We see the destruction that’s been done by people with more ambition than sense. Poverty in Ireland has made a lot of people very afraid for their future. It seems the wealthier people get, the meaner they get. When people are poor they seem to be able to share themselves with other people a lot easier. Once they have something, they have a responsibility and they don’t seem to want to deal with that responsibility. You see that in Ireland now, there's so many people with so much and with so little time to share with each other, I find that really just a shame. I thought we were really good as a country being poor, we’re not proving ourselves to be that good with money. Greed is taking over, house prices have taken over, now everyone’s mad keen to make enough money to pay the mortgage. The economy sped up and a lot of people were left behind, but a lot of people had time for each other and that was it, there was a great community, and that happens in most times there are hardship, people get together and club together. When there’s economics, people need a lot more, a lot more hanging out, a lot more getting together, people need a lot more support when their country’s rich.'

At the end of 2004, with five babies being born to the band, Kíla decided to take an 'inhalation', to record some studio albums and to reflect on seven years of 'globetrotting'.